The opening pages of the Iris Souvenir for 1851 glow with golds, reds, and greens. The hues of the new gift book competed with the flower that gave the volume its name, asserted the editor, John S. Hart, in the preface to the volume. Gift books were anthologies of light fiction, poems, and essays for the Victorian-era home. Elegant illustrations and bindings made these gift books the equivalent of modern coffee table books. The Iris made a splash by including scenes produced with an early color printing process: chromolithography.

Title page of The Iris: An Illuminated Souvenir for MDCCCLI (Philadelphia: Lipincott, Grambo, 1851)

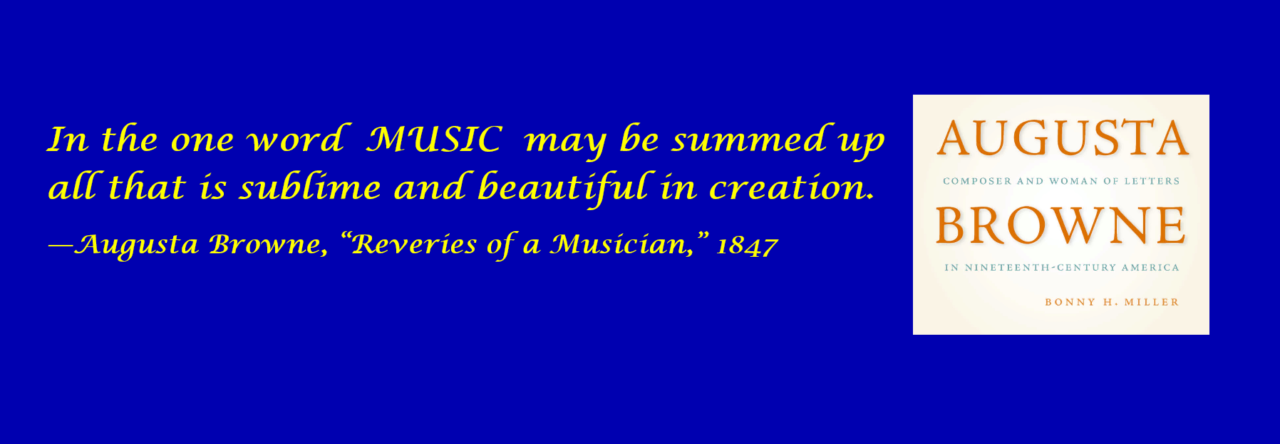

Eight of the Iris illustrations were line engravings in black and white, but Hart declared, “the four illuminated pages are printed each with ten different colors, and with a degree of brilliancy and finish certainly not heretofore surpassed.” The title page of the volume (ab0ve) is a riot of colors, flowers, and cherubs at play beneath a rainbow. Deep purple-blue is reserved for the sprigs of iris on the title page and again adorning the music for “The Iris Waltz Composed by Miss Augusta Browne” (below).

The engraved notes of music are surrounded by a drapery of flowering vines that demonstrates a feat of collaboration between a team of artists: the designer, engravers, printers, and the composer. Augusta Browne (ca. 1820–82) was a skillful keyboardist who created a compact piano solo that could fit within the flower design on a single page. The charming dance observes the usual eight-bar strains of a waltz that could be played and danced in the parlor. Not only does it sparkle with color, the Iris Waltz is engraved in a space less than four and a half inches tall and four inches wide.

The tiny notes of this little gem are nevertheless crisp and clear enough to read at the piano.

The jewel-like music page is placed close to the front of the gift book near a companion poem—“The Iris”—by Mrs. E[lizabeth] F. Swift. The eponymous poem celebrates the “sweet young spring” with its gay colors and the book itself, “another ‘Iris,’ like a star.” She describes the romantic stories and poems to follow as “poetic opals…here in loveliest union intertwined.”

Chromolithography

The Iris demonstrates how nineteenth-century lithography transformed book illustrations from black-and-white woodcuts or hand-tinted engravings to multicolored scenes. Christian Schussele (1824–79), who created the floral images that embellish the waltz, was an Alsatian painter who settled in Philadelphia around 1848. He worked with the firm of P[eter] S[tephen] Duval to handle the color printing of the Iris. The French-born Duval’s printing business used as many as seventy artists and thirty steam-powered presses.

The chemical process for color printing originated in Germany and took off in the United States after 1840. The principle behind lithography is that oil and water do not mix. Grease pencils are used to draw on limestone; after treating the stone, oily ink will adhere to it, from which paper under pressure will pick up the color and design. Each piece of paper must pass through as many print cycles as colors used in the illustration. Finely crafted illustrations for high-priced books and cards took months to complete and cost more than traditional printing methods.

Some publishers believed that chromolithographs would bring reproductions of art to a wider audience than just the wealthy elite. The style is fondly remembered for brilliant posters, sheet music covers, and nostalgic Victorian-era advertisements. Another commercial use for the new printing technique was the gift book trade in antebellum America. With lovely illustrations and a choice of bindings to fit middle- and upper-class budgets, the books made handsome Christmas and New Year’s gifts.

A Luxury Gift

When the Iris gift book was advertised in December 1850, it was priced at five dollars for the red Morocco leather binding and eight dollars for a papier-mâché cover embellished with mother-of-pearl. Five dollars would have covered a multi-course dinner for two at a New York City restaurant in 1850. Five dollars was a typical price for gift books at a time when day laborers earned not quite one dollar per day on average, and live-in domestic help earned around one dollar per week.1 Gift books were a luxury item to exhibit in the antebellum parlor.

Music was not often a feature in gift books, although it was common in household monthly magazines at the time.2 Augusta Browne contributed not just music to the Iris in 1851, but also an essay, “The Olden Time and the New,” and an essay on sculpture and painting written by her younger brother Alexander Hamilton Coates Browne (1830–50), when he had been an art student at the Brooklyn Institute in 1846. In her lighthearted essay, Augusta celebrated the legends and supernatural lore of the “olden time” compared to the matter-of-fact practicality and reasoning of her own “utilitarian era.” She asserted that traditional folklore weaves story and superstition with ancient wisdom that was in danger of being erased by common sense and utility.

The Iris was issued in editions for 1851, ’52, and ’53. The 1852 edition contained twelve colored pages to accompany the stories of Native American culture contributed by Mrs. Mary Eastman, whose husband served as a captain at Fort Snelling in what is now St. Paul, Minnesota. The edition for 1853 included a short story by Augusta Browne, “The Secret Letter,” that told a tale of romance during the Crusades. She inserted a poem by her brother Hamilton into the short story. Another brother, William Henry Browne, contributed a story of love, “The Mexican Coquette,” set during the recent war with Mexico (1846–48). How Augusta Browne became a contributor to the Iris gift books can be inferred but not proven.

The Iris Editor

John S. Hart (1810–77) directed Central High School in Philadelphia and served as author or editor for many literary works and textbooks. Professor Hart took an interest in women writers and collected representative stories and essays from almost fifty authors in Female Prose Writers of America (Philadelphia: E. H. Butler, 1851). He published the anthology as a counterpart to Female Poets of America, edited by Thomas Buchanan Read (Philadelphia: E. H. Butler, 1849), itself a competitor to Rufus W. Griswold’s anthology Female Poets of America (Philadelphia: Carey & Hart, 1849). Augusta Browne was not among the authors in these collections, but she knew many of these writers because they published in the same monthly magazines that she submitted to, including the Columbian Magazine and the Union Magazine.

Most of the authors in the Iris were women or clergymen. Among the contributors was a pair of sisters who were friends of Augusta and her brother Hamilton. Alice and Phoebe Carey came from Ohio to New York City to pursue writing. Both Careys published abundant poetry. They each wrote an elegy for Hamilton after his death at age twenty from tuberculosis. The sisters conducted a Sunday-evening literary soirée that may have included Augusta among many better-known authors of the era.

The Carey sisters could have suggested Augusta’s name to Hart or encouraged her to approach him. Whatever the method of introduction, the composer cultivated Hart’s acquaintance and sent him music as well as essay and fiction contributions. Augusta was likely the one who suggested a piece of music with a floral border as an illustration for the gift book.

Two of Augusta Browne’s previous sheet music publications featured chromolithographed illustrations on their covers: “The Family Bible” (1846) and “The Warlike Dead in Mexico” (1848). However, to set the music notation on the page as part of a lithograph was rare. This makes the Iris Waltz quite an unusual score. Perhaps the composer imagined a new presentation of music that followed the tradition of illuminated manuscripts of liturgical music from the Middle Ages but incorporated the most modern technology available in the Victorian era.

Modern Sources for the Iris Gift Book

I first saw the Iris Waltz on microfilm during the 1990s in the series American Literary Annuals and Gift Books 1825–1865, but the black-and-white xerox copy generated by the microfilm was not legible.[2] A few years later, a xerox from the Iris volume in the “Treasure Room” of rare books and special collections at Duke University was adequate to use at the piano but still not a color reproduction. A decade later, when HathiTrust digitized the Iris, the colors were enhanced to be brighter and more vivid than the original imprint. My first accurate scan of the illustrated page came from the Library of Congress around 2010.

In 2021 I acquired a copy of the Iris gift book so that I would have not only a period example of Augusta Browne’s music but also an exceptional example of chromolithography. My other Browne pieces and songs are xerox copies or digital downloads from sheet music collections (I have transcribed all this music using Finale software).

Several imprints of the Iris gift book were available from online antiquarian booksellers at the time, but I needed to ensure whether the page with the Iris Waltz was still intact in the editions for sale. The book dealer who could assure me that the music was in place was Gillian Hardy of Stray Dog Booksellers in Balnarring (near Melbourne), Australia. The bookseller could not recollect how she acquired the Iris, but the one hundred-seventy-year-old book was in good condition and made the trip back to the United States without incident.

Two additional illuminated pages appear in the Iris as well as the title and music pages. One is the list of all twelve book illustrations, and the other is the presentation plate, which in my copy is inscribed, “Presented to Ann Quayle by Mrs. Harrington.” Perhaps one day the giver and the recipient can be identified with certainty. The information might explain how this particular Iris made its way to the southeastern corner of Australia before coming home to America.

- Prices and wages from United States Commercial Register and J. D. B. De Bow and United States Census Office, Statistical View of the United States (Washington: B. Tucker, Senate printer, 1854), 164. [↩]

- Ralph Thompson, American Literary Annuals and Gift Books, 1825–1865 (New Haven: Research Publications, 1967). Of four hundred sixty-nine gift books in the series, only four include a piece of music. [↩]