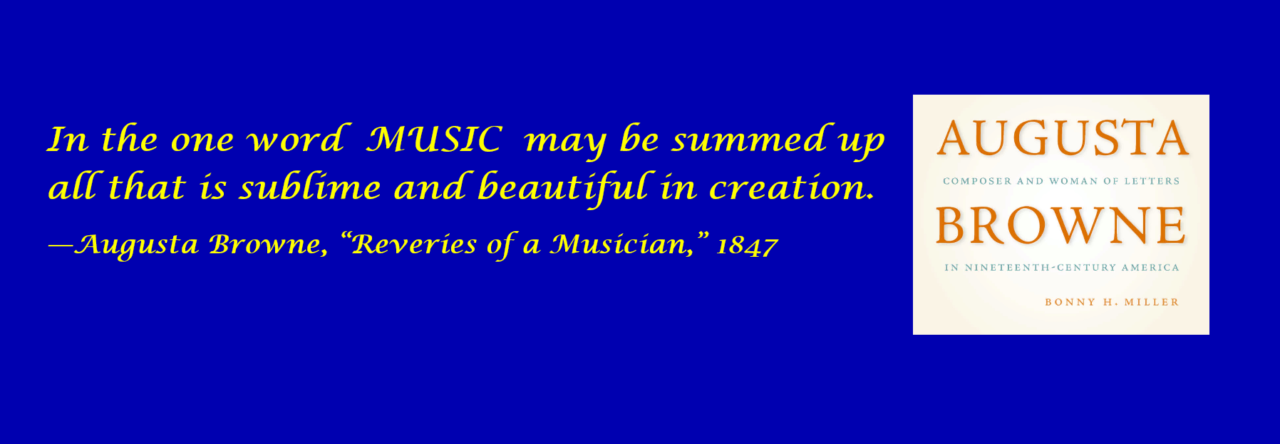

When people pick up Augusta Browne: Composer and Woman of Letters in Nineteenth-Century America for the first time, they immediately express pleasure with the look and feel of the handsome book. Next, they ask about the image on the front cover: Where is that? What city is it? The caption for the vivid illustration is on the back cover, but many will ask before they turn the book over to look for the details. The image “Broadway, New York”  was the work of Thomas Hornor (1785–1844), an English surveyor, artist, and inventor. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hornor_(surveyor). He was a master draftsman of buildings and landscapes, and he made a specialty of panoramic views. I loved Hornor’s historical view of Broadway but had to conclude that it would not be a good choice for an interior illustration for my book, since all images inside the book had to be black and white. The colors are what make the Broadway scene leap to life. When Rosemary Shojaie, in charge of design at University of Rochester Press and Boydell and Brewer, suggested the Broadway scene for a cover image, I was delighted.

was the work of Thomas Hornor (1785–1844), an English surveyor, artist, and inventor. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Hornor_(surveyor). He was a master draftsman of buildings and landscapes, and he made a specialty of panoramic views. I loved Hornor’s historical view of Broadway but had to conclude that it would not be a good choice for an interior illustration for my book, since all images inside the book had to be black and white. The colors are what make the Broadway scene leap to life. When Rosemary Shojaie, in charge of design at University of Rochester Press and Boydell and Brewer, suggested the Broadway scene for a cover image, I was delighted.

from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e9-20df-d471-e040-e00a180654d7

The glowing, hand-tinted etching shows Broadway in New York City in 1836, a spectacle that Augusta Browne experienced often during the same decade. She was a girl about ten years old when the Browne family moved to New York City for the first time (1829–33). Her parents ran a music academy at 414 Broadway in 1830. We can imagine the youngster walking with her mother among the pedestrians in the street scene depicted by Hornor. When the family returned to New York in 1841, Augusta had grown into a young woman making her debut in the commercial music world as a professional teacher, composer, and keyboardist living at 600 Broadway. She would have known every inch along Broadway through business errands, concert events, church services, and going to the homes of her students to give lessons in piano, voice, and music theory.

Hornor’s cityscape is formally described as “Broadway, New-York. Shewing [sic] Each Building from the Hygeian Depot Corner of Canal Street to beyond Niblo’s Garden.” Thus it was described by Amos Eno in his celebrated collection of images and maps of New York from its earliest days until the end of the nineteenth century. Hornor’s etching of Broadway exists in several versions. The hand-tinted colors by John William Hill (1812–79) vary somewhat from print to print. The book cover uses the brighter version in the Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps, and Pictures at the Metropolitan Museum of Art; see https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/339878. A slightly darker version is found in the Eno Collection of New York City Views in the New York Public Library; see https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e8-cf05-d471-e040-e00a180654d7.

Amos F. Eno (1836–1915) was a native New Yorker from a mercantile family that lived at Fifth Avenue and Tenth Street. Eno’s passions were the history and engravings of his beloved city from its earliest incarnation as New Amsterdam during the seventeenth century. Eno donated his complete collection of 708 rare maps and engravings to the New York Public Library in 1922. The Eno Collection continues to provide an essential resource for every historian of the city.

Use of the Camera Obscura

Hornor’s etching of Broadway captures the bustle and business of the city’s great commercial corridor. Wagon, buggies, and horse-drawn omnibuses rule the roadway while workmen and pedestrians fill the sidewalks. Businesses proliferate along the street, with advertisements for merchandise and services such as the Hygeian Depot, a “Branch of the British College of Health” at Broadway and Canal Street. Goods for sale could be hung from the tall poles that run along the curbs. Niblo’s Garden, at the corner of Broadway and Prince, hosted entertainments in an al fresco setting in addition to concerts, stage works, and exhibitions in an enclosed theater.

Hornor achieved astonishing detail and perspective by using a camera obscura, a device in which a pinhole projects an upside-down image of reality onto a screen in a dark box or chamber. Mirrors reorient the images to right side up; then, the scale and perspective of the image could be traced by the artist.

Panoramic views could be worked out with additional lenses. This portable drawing aid had long been familiar to European and British painters. Skillful practitioners could record scenes on to paper with graphlike accuracy. Early nineteenth-century cameras utilized the same pinhole principle as the camera obscura. An eighteenth-century illustration of a landscape projected by a camera obscura is part of the Wellcome Collection of digital images: https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/V0025358.jpg/full/full/0/default.jpg

Hornor (or Horner) came to New York City in 1829 after he slid into bankruptcy while trying to carry out an enormous panoramic diorama of London as seen from the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral. His grand plan to create a city diorama in a special exhibition building in Regent’s Park followed early successes as a “pictorial delineator” who created illustrations of estates of England’s wealthy gentry. London’s loss became New York’s gain. Hornor remained in the United States for his remaining fifteen years.

The View from Brooklyn

A different panoramic view illustrates New York City from the perspective across the water. “New York from Brooklyn Heights” dates from the latter 1830s and is again part of the Eno Collection at the New York Public Library. This impressive aquatint was painted by John W. Hill, who had been a collaborator with Hornor on “Broadway 1836.” The scene was engraved by William James Bennett and published by L. P. Clover, New York; see https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e9-20df-d471-e040-e00a180654d7#. Again, this was a view that Augusta Browne would have known well from her days in New York City. The family lived in Brooklyn Heights during 1842–45, when Augusta served as organist at First Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn.

Hill’s sweeping vista of “New York from Brooklyn Heights” shows the cityscape across the water with a further view of the distant hillsides of New Jersey. A tiny family of four clad in late Georgian-era clothing takes in the view from a housetop balcony overlooking the East River. The gentleman holds a telescope to magnify the distant buildings of the city. The slender finger of Manhattan seems almost too narrow to hold so much commercial activity. Hornor made a similar attempt to depict New York from Brooklyn (also in the Eno Collection; https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e8-94a0-d471-e040-e00a180654d7), but his engraving feels cluttered and lacks the charm of Hill’s idyllic river study.

The detailed panoramic image of Manhattan across the water includes a guide to the tallest buildings in the cityscape. Across the bottom of the print are approximate indications to locate Merchant’s Exchange, Grace Church, Trinity Church, Wall Street Church, and the Custom House in lower Manhattan. The scene continues with the City Hotel, Middle Dutch Church, Holts Hotel, St. Paul’s Church, Fulton Market and Ferry, and Aster House. The many church steeples provided the most obvious landmarks for viewers. Continuing up the peninsula are Clinton Hall, St. George’s Church, Brick Church, Murray Street Church, City Hall, the Hospital, Christ Church, French Church, St. John’s Church, the Hall of Justice, and St. Mathew’s Church. Hill’s view is a triumph to fit in so much detail while maintaining an airy, playful ambiance.

Brooklyn to Broadway and Back

The Browne family moved back to Manhattan after Augusta parted ways with First Presbyterian in 1845. The church was in the process of building a new edifice on Henry Street, where it remains to this day. The old building and the organ were sold, and Augusta resigned, not without some hard feelings that she expressed in the Brooklyn Evening Star. Back in the city, she lived at various addresses including 469 Broadway, as well as nearby on Broome and Crosby streets during the 1840s. The decade between 1845 and 1855 was a productive and successful period for Augusta Browne as a composer, teacher, and author.

When Augusta married in 1855, her husband—artist John W. B. Garrett—maintained a portrait studio at 709 Broadway. In 1857 her parents bought a house on Adams Street in Brooklyn, close to the current site of Cadman Plaza Park and the Brooklyn Bridge (opened in 1883). When the Brownes moved in, Adams Street was a pleasant residential avenue. The house had amenties including gas lighting and a yard with an arbor. There was plenty of room for the grandchildren that they anticipated. The recently married couple soon joined them in Brooklyn. Sadly, Augusta’s husband died abruptly from heart failure in 1858. They had no surviving children.

Augusta and her parents continued living on Adams Street as the Civil War erupted. The tight knit family left the New York State near the end of the war to be close to Augusta’s brother William Henry Browne in his military assignment in Baltimore. They relocated a second time when William Henry went to work at the Patent Office in Washington, DC, in 1868. Augusta never moved back to Brooklyn or New York City after the Civil War.

More Images of New York City

The compendium of images in the Eno Collection of New York City Views is a treasury of New York City history. Famous historical venues leap to life through the collection images even though many sites have long since been demolished to make way for the new. The complete Eno collection is available to enjoy at the New York Public Library at https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/collections/the-eno-collection-of-new-york-city-views#/?tab=about.

Hornor’s vibrant depiction of Broadway inspired an essay by Andrew Gardner titled “The Spectacle of Commercial Chaos and Order: Thomas Hornor’s View of Broadway and Canal Street, 1836.” https://visualizingnyc.org/essays/the-spectacle-of-commercial-chaos-and-order-thomas-hornors-view-of-broadway-and-canal-street-1836/. Gardner’s research essay is part of Visualizing 19th-Century New York, a remarkable digital exhibit produced by the Bard Graduate Center: https://visualizingnyc.org/. Interactive period maps and images, accompanied by detailed essays, transport us to the Big Apple of Augusta Browne’s lifetime.

Visualizing 19th-Century New York provides a detailed look at one hundred years of the cityscape. The Eno Collection chronicles three centuries of New York history. Together these digital collections present the evolution of America’s great iconic city.