Who was J. W. B. Garrett, whom Augusta Browne married in September 1855, within weeks of first meeting him?

J. W. B. (John Walter Benjamin) Garrett was an artist who specialized in portraits, especially paintings made from small daguerreotypes, just as families today can commission a portrait to be painted from a photograph. Augusta Browne never revealed how they became acquainted. The connection might have occurred through an introduction at an art gallery, at church, a concert, or through mutual acquaintances at the Home Journal, in which Augusta published stories and Garrett advertised his services as a portraitist. Garrett exhibited a portrait of William Henry Browne, the composer’s younger brother, at New York City’s National Academy of Design in 1857. It seems plausible he would have made a portrait of his new wife, Augusta, but no evidence proves its existence.

Garrett had not trained as an artist and turned to painting around 1850, after chasing journalism and politics as a young man. John (J. W. B.) did not hail from New York. He arrived in Gotham during the summer of 1855, after traveling from Memphis, Tennessee, where he had recently lived and maintained a portrait studio.

Garrett was five years younger than his bride, although Augusta may never have admitted her true birth year to him. She preferred people to think she was just a year or two older than her brother William Henry Browne (born 1825), who was about the same age as Garrett.

North Carolina Roots

John impressed people as a polite, well-spoken young man. The Home Journal described him as “a fine fellow…with the genial, courteous manners of the sunny south.”(([“Mere Mention. An Artist’s Studio,” Home Journal, November 1, 1856.)) The artist came from North Carolina, where John’s father, Martin R. Garrett, had tried to scratch out a living from farming and teaching. The financial panic of 1837 wiped out Martin’s investment in mulberry trees to raise silkworms, a short-lived fad that collapsed like the Dutch tulip mania in the seventeenth century. John’s father decided to sell his land and equipment in order to move his family to Tennessee, where newly available farmland in western Tennessee had been ceded in 1830 by the Choctaw Nation in the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek.

Martin Garrett had been a student at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill for one or two years and considered it his alma mater (class of 1818), although he never graduated.((University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Sketches of the History of the University of North Carolina, together with a catalogue of officers and students, 1789–1889 (Univ. of NC, 1889), 129.)) His oldest son, Samuel (b. ca. 1821 or 22), spent two years at Yale.((Calliopean Society, Catalogue of the Calliopean Society: Yale College, 1839 (New Haven, 1839), 23.)) The next son, William (b. ca. 1823), began studies at Chapel Hill and eventually trained in homeopathic medicine.((William D. Garrett to Pres. James K. Polk, March 11, 1847; https://www.loc.gov/resource/mss36509.049_0010_0844/?sp=57&st=image (images 57–59).)) Both sons seem to have left college at the time of the financial panic and the family relocation to Tennessee.

The elder Garrett did not prosper much better in Tennessee than in North Carolina. There was no money when the third son, John, became old enough for college, nor for his two younger brothers. Despite financial straits, the Garretts owned a few slaves, in part because John’s mother had inherited them from her parents. In turn, she willed her slaves to be divided among her seven children. John and his siblings shared ownership of five or six enslaved men and women after their mother’s death around 1840. This was the subject of a court case argued before the North Carolina Supreme Court in 1842/43, in which creditors of Martin Garrett attempted to seize the slaves to settle his debts.((Reports of cases at law argued and determined in the Supreme Court…, Vol. 3, 459–66.)) These enslaved workers traveled with the Garretts to Tennessee. Not surprisingly, the family politics were solidly southern, Democratic, and pro-slavery.

Journalism and Politics

His father’s declining fortunes made it clear to John that he would have to forge his own path in life. As a teenager, he drifted from Tennessee back to North Carolina, close to kinfolk and families from his childhood. Even without any college education, John was a bright and resourceful young man who could have secured some work as a clerk or teacher. He found an opportunity to combine his skills and background with the local newspaper press in North Carolina. John embarked on journalism as editor of the Louisburg Union in 1847, which he converted from a neutral paper into a partisan Democratic advocate.

His next enterprise was to establish a weekly paper in Hillsborough (Orange County), NC, the Orange Ratoon, in 1848, which Garrett described in the prospectus as “thoroughly Democratic: devoted to that system of national policy originated by the immortal Jefferson, sanctioned and defended by the inimitable Jackson, and now being carried into effect, and maintained with zealous ability, by the much abused, but, nevertheless, indefatigable, wise and patriotic President of our Republic James K. Polk.”((The prospectus of the Orange Ratoon was published in the North-Carolina Standard and the Tarrboro Press several times during March and April, 1848. A ratoon is a new shoot, such as cotton or sugar cane, that grows from remaining roots and stubble after harvest.))

The young editor signed himself as “J. W. B. Garrett” from the start, and he continued to use these initials consistently through the rest of his life. With this distinctive identifier, there is no confusing him with John W. Garrett (1820–1884), the influential businessman who would become the director of the B&O (Baltimore and Ohio) railroad.

During the summer prior to the 1848 election, J. W. B. Garrett served as a delegate from North Carolina to the Democratic convention. His hopes for the future apparently rested on gaining some kind of political patronage from a winning candidate. Following his convention trip to Baltimore in May, John stepped away from the Orange Ratoon in September, owing to “ill health,” yet he continued to campaign for Democratic candidates in North Carolina during the fall election.((Raleigh Weekly Standard, Nov. 1, 1848.)) Unfortunately, none of his candidates won office, and his hopes for a political appointment were dashed. He only managed to obtain a three-month contract as a federal clerk in Raleigh, NC, during 1849.((Senate, Report of the Secretary of State, Showing the Names and Compensation of the Clerks and Other Persons Employed in the Department During the Year 1849, 31st Cong., 1st sess., 1850, S. Ex. Doc. 29, 2.))

Return to Tennessee

After his disappointments in North Carolina, John returned to Macon, Tennessee, in 1850, where he took orders for the Southern Literary Messenger, a monthly literary magazine known for its lineup of notable American authors.((“General Collectors for the Literary Messenger,” recurring notice, Southern Literary Messenger, vols. 15 and 16, 1849 and 1850.)) During the same period, an article titled “Singular Case of Monstrosity. By J. W. B. Garrett, M. D., of Macon, Tennessee” was published in The Western Journal of Medicine and Surgery.((The Western Journal of Medicine and Surgery 6, no. 1 (July 1850): 1–6.)) The article—studiously couched in medical terminology by “Dr.” J. W. B. Garrett—described a newborn resembling an elephant delivered from a woman who had seen an elephant during pregnancy.The tongue-in-cheek article suggests the spirit of a prank, or even some ill will towards his brother, the homeopathic physician.

J. W. B. Garrett began his second career as an artist around 1850. He was apparently self-taught to this point but may have fraternized with more skilled portraitists in Memphis and Cincinnati to learn the craft of painting. By 1852 he listed himself as an artist in Cincinnati, where he painted a portrait of Judge Stanley Matthews, then a young lawyer newly appointed to the Ohio Court of Common Pleas, but who would one day serve on the U.S. Supreme Court.((“A Specimen of the Arts,” [Cincinnati] Daily Enquirer, Aug. 28, 1852.))

When business ebbed in Ohio, he traveled back to Tennessee and Alabama to seek commissions. John rambled from town to town, probably using his charm and savvy to cultivate clients up and downriver from Cincinnati to Memphis. He frequented hotels, theaters, and probably riverboats where he could have located potential clients. Among his portrait subjects was the Spanish dancer, Pepita Soto, who performed in Memphis during March 1854. The work was praised as “inimitable” and “universally admired for its fidelity with the original” by the Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer.((“Garrett’s Portrait Gallery,” Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer, April 7, 1854.))

Garrett also sought out parents who might crave a respectable portrait of themselves or their children. Newspapers mentioned his “exquisite” depiction of “a young girl of Memphis just blooming into womanhood.”((Copied from the Louisville Journal in the Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer, May 15, 1855.)) John seemed to find steady business and success in Memphis, where he advertised “daguerreotype copies as large as life, and no extra charge made.”((The ad ran for twelve months in the Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer, May 16, 1854. The ad also appeared regularly in the Memphis Daily Appeal.))

Portrait by J. W. B. Garrett

Few of Garrett’s paintings have survived to the present day. A single example, the “Portrait of a Memphis Lady,” has circulated on the internet since 2017, as the owners of the painting tried to discover the identity of the female subject after purchasing the work at an estate sale. Since Garrett’s paintings were commissioned by families for private homes, where they may have hung for many decades, more of his portraits may become known through estate sales in years to come.

The National Society of Colonial Dames of America in Tennessee posted the image of Garrett’s “Portrait of a Memphis Lady” online as part of their Tennessee Portrait Project. The rear of the painting bears the signature, “Painted by J. W. B. Garrett 1853.” The painter’s technique is smooth and assured in this depiction of what appears to be a middle- or upper-class widow dressed in black. The unnamed Memphis woman may have been painted from a daguerreotype. Her solemn expression suggests recent loss or widowhood. The rosy color in cheeks may have been the artist’s effort to enliven her somber face. Garrett skillfully shows the sheen of the fabric of her gray shawl and the texture of her lace collar. The same elegance had been noted about his portrait of Pepita Soto, “the fineness of the drapery of the painting will be remarked by all who see them.”((“Garrett’s Portrait Gallery,” Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer, April 7, 1854.))

John Garrett conducted his business from the United States Hotel in Memphis, before relocating a studio space in the rear of the “store of Cossitt, Hill & Tallmadge, where he will be pleased to receive visitors, and have them look at his pictures.”((Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer, May 16, 1854.)) Garrett liked to cultivate potential clients in a relaxed social atmosphere.

Garrett Family Matters

Memphis sits in Shelby County, adjoining Fayette County, where Garrett family members lived. John’s father, Martin Garrett, probably died around 1851/52, and a younger brother, George W. Garrett, died in 1853 in his early twenties. John seems to have become the de facto guardian of his little sister, Lucretia (b. ca. 1833), after these deaths. He and his siblings still owned several enslaved men, women, and children. There is no evidence that these enslaved served in John’s workplace or attended him at home or when he traveled. Instead, he hired out these people to work for others. In 1855 the Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer advertised, “For Hire, A sprightly Negro Girl, about 15 years of age; a good House Servant. Apply to J. W. B. Garrett.” A week later, the paper announced, “For Hire, A No. 1 Negro Woman—a good cook, washer and ironer. Apply to J. W. B. Garrett.”((Memphis Daily Eagle and Enquirer, April 7 and 13, 1855.))

These enslaved women belonged, at least in part, to John’s sister, Lucretia, who granted power of attorney to her brother J. W. B. Garrett for the sale of a slave.((November 29, 1855; Shelby County [TN] Register of Deeds, Book 0022, p. 405.)) For “Eight Hundred Ninety five dollars… [ Garrett] bargained and sold and conveyed to John H. Brinkley his heirs and assigns a negro girl named Lucy, aged about sixteen years.((Power of attorney dated November 29, 1855; sale conducted Dec. 31, 1855, and recorded Jan. 1, 1856; Shelby County [TN] Register of Deeds, Book 0022, p. 405.)) She was evidently the fifteen-year-old advertised “for hire” as a “sprightly” girl and a “good house servant” in the Memphis Daily Eagle the previous year.

Disaster Converted to Opportunity

A disaster unfolded when fire completely consumed John’s studio and paintings on December 12, 1854. The news was notable enough to be reported in out-of-state newspapers: “The studio of Mr. Garrett, an artist of Memphis, was destroyed by fire on Tuesday morning. Loss $3,000, insurance $1,500.”((Baltimore Sun, Dec. 16, 1854; Evansville Daily Journal, Dec. 16, 1854; Charleston [SC] Courier, Dec. 19, 1854.))

With the insurance settlement of $1,500—worth some tens of thousands of dollars today—John was upriver in Louisville by January 1855, and before long in New York City, “which he intends to make his residence during the summer and will be happy to receive calls at his studio,” according to the Home Journal (August 4, 1855). John found a friendly response at the Home Journal as he launched his New York portrait studio. But he had the responsibility of his frail sister, who was already in decline from tuberculosis. In September John married Augusta Browne after only a month or two of acquaintance. We can imagine that those who knew Augusta and her family were surprised when she married so hastily, and to a younger man with scarcely any professional reputation in the city.

Well established as a music professor since 1841, Augusta had lived in the thick of New York City throughout her twenties and regularly attended venues where she could meet eligible men, both young and old. She interacted with the families of her students, including older brothers, relatives, and household friends. Augusta maintained ongoing professional relationships with men who were authors, editors, newspapermen, clergymen, painters, and music and art lovers. She could have married earlier, but the simplest way to maintain her professional career was the route of a respectable spinster who taught, performed, composed, wrote, and published.

Garrett participated in the New York art scene as he worked to establish his studio. He showed portraits in exhibitions of the National Academy of Design in 1857 and 1858, although he was never elected as an academy member.((National Academy of Design and Mary Bartlett Cowdrey, National Academy of Design Exhibition Record, 1826–1860, 2 vols. (New York: New York Historical Society, 1943), vol. 1, 177.)) One of his sitters was Augusta’s brother William Henry Browne, who was a lawyer in New York City. It seems likely that Garrett would have also done a portrait of his new wife, but no such painting is known to exist. The names of Garrett’s portrait subjects were not specified for five of the six works he showed at the National Academy of Design.((Garrett’s “Portrait of a Memphis Lady” is the only work by the artist currently available.))

How much Garrett’s Democratic party sympathies became an issue in the Republican household of the Browne family is an intriguing question. His brother-in-law William Henry Browne was very active in the new Republican party during the 1850s and campaigned for its first presidential candidate, John C. Frémont, in 1856, during Augusta’s first year of marriage to John Garrett. Vigorous debates, if not arguments, must have taken place at the Browne home. Democrat James Buchanan of Pennsylvania won the election and served as president until Abraham Lincoln took office.

In 1857 the Browne family, or at least Augusta’s parents, decided to buy and relocate to a new home in Brooklyn at 222 Adams Street, a house with a yard and space for grandchildren. Roughly thirty-five at the time of her marriage, Augusta was not too old to have children, but her age limited her to no more than two or three at most. While Augusta may have become pregnant and miscarried, there is no vital record of any birth or death of an infant during her marriage.

Financial Panic of 1857

The financial panic of 1857 hit hard for both Augusta and John. He lost patrons and she lost students due to the commercial depression. The awkward logistics of serving Manhattan families for music lessons or portrait commissions complicated their lives after the move to Brooklyn. The unavoidable commute by ferry and horse-drawn trolley to John’s studio at 709 Broadway cut short the social lifestyle that he formerly pursued to find urban customers.

In spring, 1858, John visited North Carolina, reconnecting with relatives and family acquaintances to seek commissions for portraits. Announcements of his arrival in Tarboro, NC, mentioned travel to the south “partly for his health and partly professional.”(([Tarboro] Southerner, April 10, 1858.)) Allusions to illness and convalescence had popped up in newspaper accounts of John since 1848. Perhaps he sometimes used “ill health” as a convenient excuse or explanation for changes of direction in his life, but John may have had serious underlying health issues.

Poor health and early deaths haunted the Martin Garrett family. His wife’s will of 1840 noted seven children. Of those who did survive childhood, both George and Lucretia died in their early twenties, likely from tuberculosis. Samuel and John passed away in their thirties, relatively young, but possibly weakened by serious infections like strep throat and rheumatic fever. The fate of the three other Garrett siblings is unknown.

In 1857, not quite a year before John’s death, Augusta wrote, “A dark and crying sin that is laid at the door of artists in general is the unpardonable one of poverty.” She lamented the struggles of so many poets, composers, and artists to earn even a meager living. Her essay “Crotchets of Comfort for ye Seekers of Fame” argued that, rather than a liability, “poverty seems to be the hotbed of genius.”((New York Musical World, 18 #340 (Oct. 3, 1857): 631.)) The article may have been written in support of her husband’s artistry, or in his defense when the portrait business faltered amidst the economic downturn.

As his New York prospects dried up during the Panic of 1857, John Garrett was mentally stressed, and possibly physically ailing, when he experienced fatal cardiac arrest on a hot summer day in late August. In the summer temperatures, burial had to take place quickly. The announcement on August 28, 1858, in the New York Herald offers the only details about his death: “Garrett—Suddenly, in Brooklyn, on Thursday, August 26, of disease of the heart, John W. B. Garrett, late of North Carolina, in the 34th year of his age. Funeral from the residence of D. S. Browne, 222 Adams Street, Brooklyn, this afternoon, at three o’clock. Friends are invited to attend without further notice.”

The service at the Browne home on Saturday was followed by interment at Green-Wood Cemetery. On the tombstone is carved “My Husband / John Walter B. Garrett” on one side and “My Sister / Lucretia A. M. Garrett” on the other. The remainder of the lettering has worn away.

Legacy

J. W. B. Garrett’s wits and talents took him on a long journey in an all-too-short life. Out of necessity he sought opportunity and risked failure. When one avenue dwindled, he redirected and redefined himself, from young man in search of a white-collar job and political wannabe to aspiring artist.

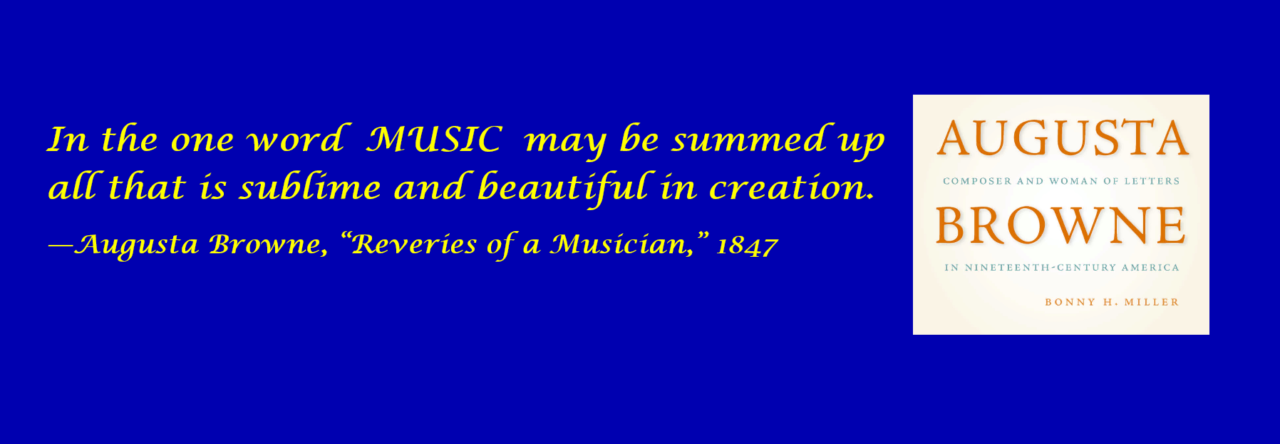

In 1859 Augusta Browne Garrett published The Precious Stones of the Heavenly Foundations, a book of devotional selections, some her own work and others selected from sermons by well-known ministers. The manuscript was completed and dedicated to the memory of her husband within a few months of his death. She included a poem by her late husband, “Reveries in a Forest of North Carolina,” as well as a song, “The City of Delight,” with words by St. Augustine and “Music by the late John Walter B. Garrett / Arranged by A. B. G.”((See also transcription in Bonny H. Miller, Augusta Browne: Composer and Woman of Letters in Nineteenth-Century America (Rochester NY: University of Rochester Press, 2020), 158.))

The book received positive reviews in many periodicals.((Reviews appeared in such periodicals as the Evangelical Repository, Methodist Quarterly, Christian Review, and newspapers including the Boston Evening Transcript.)) Such volumes of “polite literature” found a place in many parlors, and words of consolation for the bereaved were always in demand during an era of early mortality. More copies of The Precious Stones are found in libraries and archives than any of Browne’s sheet music publications. Born of loss and grief for J. W. B. Garrett, The Precious Stones of the Heavenly Foundations would become Augusta Browne’s best-selling publication.