Introduction

The title page of The Lady’s Almanac for 1854 showcases a romanticized illustration of a lady writing with a quill pen at an ornate desk as time slips away in the winged hourglass.

Augusta Browne’s table and chair would have been far less grand than the engraving depicts, but she was already making contributions as a writer as well as a composer. On page 92, the almanac includes her name—lacking (as often happened) the final e of Browne—among noted American women writers.

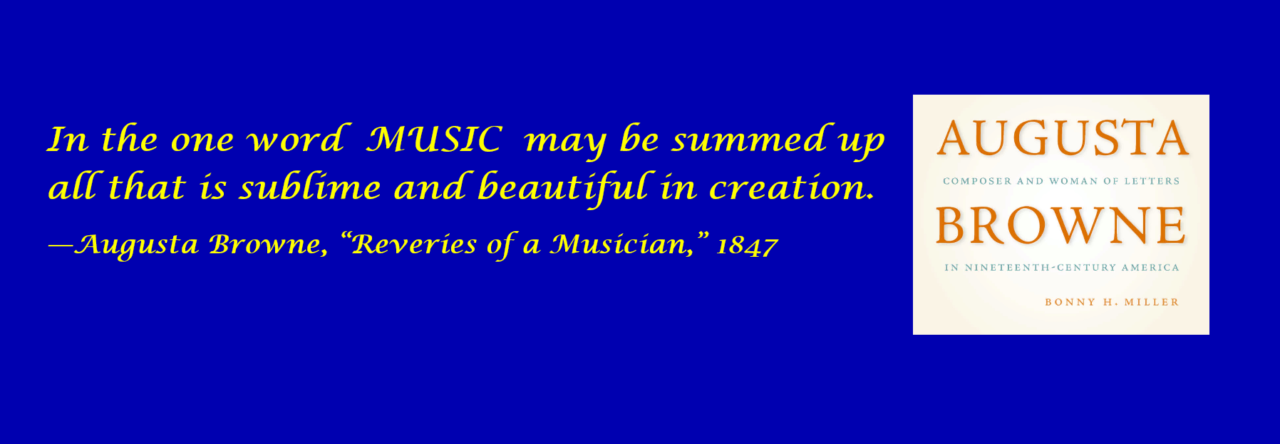

The following sketch, “Paper and Pen,” imagines an afternoon of writing as Browne battles distractions to work on an essay that she published in 1847. The setting of Browne’s bedroom as her writing venue echoes Virginia Woolf’s 1929 essay “A Room of One’s Own,” in which the British author asserts, “a woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write.” Augusta Browne (1820–1882) earned income primarily as a music teacher. In addition, she had a room of her own, even if—like her fellow author Emily Dickinson (1830–1886)—that room was in her parents’ house. Details from Browne’s 1847 publications in the Columbian Magazine anchor the fictional scene.

Paper and Pen

Lace curtains fluttered at the window as shouts rose from the streets. New Yorkers spoke in a jumble of accents and tongues: hawkers selling fruits and greens, teamsters yelling at their draft horses, babies howling in nearby apartments. Augusta Browne smiled when she heard the notes of a piano from a residence farther down Broome Street. Stumbles and hesitations slowed the waltz to a crawl. Someone needs a music teacher, she thought.

Sounds like a child, maybe that little girl who wears a yellow bonnet like her mother’s. I could stop by and leave my card. The lady looks too well off to be a dressmaker. Maybe the missus asked the seamstress to make a lookalike bonnet for her daughter.

Augusta recalled when she had a new dress made from the same delicate blue fabric as her mother’s. Even the lace was the same along the neck and puffed sleeves. Only ten at the time, she remembered feeling so grown-up and pretty in the dress when she walked hand-in-hand with Mama to the shops along Broadway. The Irish seamstress had told Augusta strange tales of fairies and spirits during the fittings. She stood motionless while she took in every word. The dressmaker’s stories frightened and fascinated her at the same time. Mama laughed and said that she had heard the same stories when she was growing up in Dublin.

Her daydream reminded Augusta that she had mending of her own to do as well as errands to run. She sighed as she came back to earth. It was a rare afternoon when she had no music students to teach, but there were letters to editors and publishers that must be sent. And she needed to work on the article that she was writing for the Columbian Magazine. “Reveries of a Musician” was a loose enough theme to weave together many ideas from music, art, history, and literature. The first part of the essay had come out in July 1847, and now she was working on the conclusion for the October issue.

Ready or Not

A pile of long sheets of foolscap awaited, held down by her prized ebony pen box with mother-of-pearl inlay on its hinged lid. For years Augusta had used an empty cigar carton to hold her writing supplies, but this jewel-like box had been a gift from her brothers Louis and St. John, who worked in the piano building business in Boston. Such elegant goods arrived regularly on the merchant ships coming into Boston harbor from the Far East. Augusta often traced the inlaid design on the cover with the fingers of her left hand, as she thought about what to write next, the pen poised aloft in her right hand.

She placed an empty page into position beside the blotter. As Augusta picked up the box to select a pen nib, a leaf of paper escaped from the pile beneath and sailed across the room to land on her bed. The sheet of paper lay askew on the carefully folded bedspread. Its whiteness kept catching her eye as she tried to focus on the article at hand. Hubbub from below, mixed with odors of fresh-made bread coming from the bakery and onions frying for somebody’s midday meal, added to the distractions. She stood up from the straight-back wooden chair and stepped across the room to retrieve the errant page.

Her pen lay ready and waiting, but her wide skirt knocked against the desk as she sat down. The pen tumbled to the floor, leaving a splotch of black ink on the wood. Thankfully, it had not fallen on her dress or on the braided rag rug beside the bed. Augusta used the piece of flyaway paper in her hand to wipe up as much of the mess as she could. She balled up the sheet and scolded herself that time was ticking away.

Outside the door, the cat cried and scratched to be let in. Augusta tried to close her ears to the plaintive mewing. The bright hours of morning sunlight spilling through the window would be over all too soon, replaced by shadows cast by the four- and five-story brick buildings across the street. She hated to light the oil lamp during the daytime. Her writing never flowed as easily under lamplight as in sunshine.

Finding the Words

Pen firmly in hand, Augusta tackled another blank sheet from the stack of paper. She made a brave start, writing, “Old songs, the precious music of the heart, who does not love them?” Just such a song, “Gramachree,” ran through her mind. The Gaelic phrase meant “love of my heart.” She hummed the Irish folk melody, thinking of the sad but tender words Thomas Moore put to the tune: “The harp that once through Tara’s walls the soul of music shed.” Most people sang the song with Moore’s English words, but the original lyrics had been in Gaelic. Neither Augusta nor her parents spoke Gaelic, but, like most Anglo-Irish Protestants, they were familiar with many expressions and sayings from the ancient language.

Augusta could not remember Ireland, where she had been born more than twenty-five years earlier, just a few months before her parents left Dublin for North America. Still, she imagined an ancient castle of gray stone etched with moss and lichens. She envisioned men and women in colorful medieval garments filing past the walls amidst great, looming oak trees. A minstrel carried his harp toward the courtyard where people were gathering to listen to his songs.

A volley of street noise interrupted her reverie, as horses neighed, and men argued about who should go first and who was blocking the road. A shaky soprano who lived down the street had begun to warble a song about “Fanny in the Dale.” An organ grinder cranked out a different tune at the intersection below.

Augusta shook her head. I really should write about the sounds of my neighborhood. They could tell quite a story. But not today.

Carolan’s Concerto

She reached across the desktop, closed the window, and settled down to the almost-empty page. A chain of memory soon linked her thoughts from the traditional songs of Ireland to the pieces she had learned from her parents during her earliest piano lessons. “Carolan’s Concerto” had been a mighty feat to master with her tiny hands and fingers, but how wonderful it sounded when she played it in a duet with her mother or father.

Turlough O’Carolan (1670–1738) had been a great Irish harper, the most famous of the itinerant minstrels who played the harp and sang at the stately homes of gentry around the countryside. His beloved tunes and dances were passed down among Irish fiddle players.

Thoughts of cherished songs and associated memories ignited her pen. “The old familiar lays,” she wrote, “round each of which cluster a thousand treasured recollections.” Memory and music were bound together in “strains of other days” that can unlock loves and sorrows from youth and the distant past. She described the power of patriotic anthems over their countrymen, and of national songs that could rally soldiers to battle or reduce men to tears of sadness. Ideas raced faster than she could write them down.

By the time the maid knocked at the door to announce that tea was ready, the ink was drying on several full sheets strewn about the tabletop, and shadows were advancing across the page before her. Augusta stood up, stretched, and shook the cramp out of her fingers and wrist. How music carries us to other times and places, she marveled, as she wrapped the woolen shawl snugly around her shoulders. She opened the bedroom door and descended the stairs.

Living with her parents offered certain advantages. The arrangement fulfilled the social mores of respectability for a young, unmarried woman who worked as a music teacher and church organist. A steaming cup of strong tea that materialized from the kitchen each afternoon was another benefit. Augusta looked forward to the sharp tang of the black tea as it blended and mellowed with the addition of silky cream and sugar. As she entered the parlor, she could see her mother was already pouring from the teapot into the white-and-gold china cups at the dining table.